Corporate Venture Capital & Healthcare

This is the first BHC post in a series to give a glimpse into our Comparative Investing Strategies conference panel. The views expressed are solely those of the authors, with significant data sources leverage from CB Insights, Correlation Ventures, and DowJones VentureSource. We hope to see you at the 2020 Business of Healthcare Conference on January 25th. Get your tickets before they sell out!

VC & CVC overview

Venture Capital (VC) is a broad topic, but we will attempt to dive into a subset of VC, Corporate Venture Capital (CVC). Before we get there, we’ll provide a brief overview of traditional VC and then a deeper dive into CVC within healthcare. The traditional VC model is highly speculative at best given the likelihood of failure of any individual start-ups, but the ecosystem is highly impactful for future innovation across many industries. For those not familiar, a VC firm raises a fund from Limited Partners (LPs), and charges VC management fees and carry which are typically 2% of assets under management (AUM) and 20% carry or carried interest (share of profits realized by a fund). A VC fund can charge the typical “2 and 20” by deploying capital across an array of startups hoping to make a healthy financial return. Realistically, VCs understand that the fund often sees its returns driven by a few with excellent investments while acknowledging that most will yield modest to poor returns. See Figure 1 (above), which illustrates a less-than-favorable distribution of over 20,000 companies from 2004-2013. The high-risk nature of a start-up makes it exceedingly difficult to “win” in the venture game, particularly over multiple funds unless a VC has specific differentiators, such as a higher than average deal flow volume or simply higher quality deals - based on their brand recognition, networks, or track records (e.g., Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia Capital, or Bessemer Venture Partners). The goal of a traditional VC is simply to make money on its investments upon liquidation, through either sale to a strategic or an initial public offering (IPO). From finance classes in business school or by following public markets, readers may recall that IPOs can be wildly successful or challenging, and are usually volatile. Where CVCs differ from traditional VCs can be largely bucketed into (1) financial incentives and (2) strategic incentives.

Financially, CVCs are not generally accountable to LPs because they are usually funded through a company’s balance sheet - which can lead to a whole different conversation on CVC & accounting. Additionally, the managers of a CVC are typically not incentivized by management fees or carry, though there may be performance bonuses based on fund return or revenue contributions. A CVC manager is more reliant on a corporate salary compared to a traditional VC manager. This creates slightly different incentives and daily responsibilities, as traditional VC partners may balance LP meetings when raising a fund, a CVC manager must engage numerous stakeholders continuously: business units, corporate strategy groups, CFO investors, and general corporate bureaucracy.

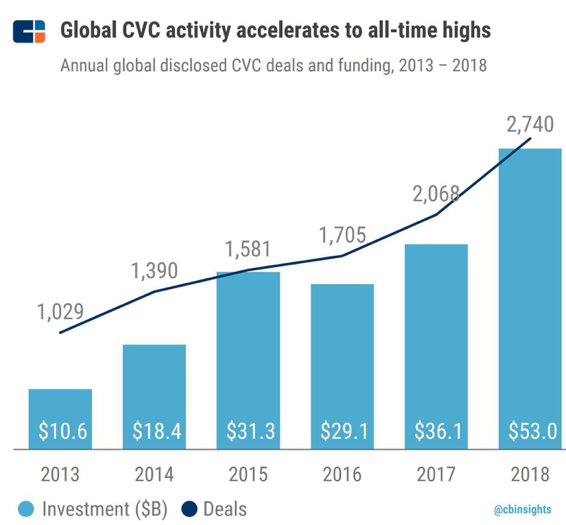

Strategically, the purpose of the CVC arm for any firm is to generate new sources of broader enterprise innovation via small bets on start-up technologies and teams that the parent company is technically or financially unwilling or disincentivized to internally develop. The ultimate goal of a CVC is to identify future businesses of strategic interest, usually in their core market, though not necessarily, to then acquire the business or the IP portfolio. In this way, a strategic might be able to move more quickly through external innovation rather than slowly drag its way through internal steps obtaining corporate funding for slow-moving, costly R&D projects. In addition, misaligned incentives for employees to work on innovative projects present a persistent problem (i.e., startup employees often grind in hopes of a big equity payout on exit, whereas corporate salary compensation may not spark the same bootstrapped, round-the-clock working mentality). The longest bull market in stock market history and a cultural “cool” factor associated with entrepreneurship and VC are contributing to a capital availability and general CVC model acceptance. Figure 2 (above, left) “Global CVC activity accelerates to all-time highs”, illustrates how drastically capital deployment and investment activity are increasing. Figure 3 (above, right): “CVC contribution to the overall VC ecosystem grows”, illustrates how CVCs specifically are slowly inching their way into the broader VC ecosystem, again, likely driven by a bull market and excess cash produced by the core business, in addition to continual pressure on executives to innovate to get ahead of competition stealing away market share. It is likely a combination: established CVCs are contributing more aggressively, and new CVCs are forming, as seen in Figure 4 (below): “Swarm of new CVC groups are investing for the first time”.

Healthcare specific CVC

Zooming in from Global CVC activity (~$53B in 2018) to the healthcare sector, we hone in on a sector representing roughly 20% of all CVC (Figure 5 (left): ~$11B in 2018). The question then becomes: “Is the healthcare sector behaving like other sectors?”. The answer is complicated. There is global variation in healthcare spend, and different methodologies to appropriately map spend to output. If we consider current health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), we know the U.S. is roughly ~17% and growing, but globally it was ~10% in 2015 according to the World Health Organization (WHO). We acknowledge this metric may not be the best proxy for whether healthcare CVC vs. all CVC is appropriate, but we can likely conclude that CVC investment healthcare innovation is “hot” at ~20% and increasing. How sustainable is this trend? Only time will tell. A market correction could quickly dry up investment capital.

Healthcare sub-sectors

Diving in further, there is ample publicly available data across Pharma, Medical Devices, Payer, Provider, and digital health to understand sector- and sub-sector level activity. Digital health is perhaps the most visible sub-sector, as seen in Figure 6 (right) “CVC investment to digital health startups inches higher”. (1) Increasing visibility and salience of American health system issues and (2) the reduced capital required for a digital start-up are both prompting entrepreneurs to tackle problems using mobile and online platforms. Companies like Livongo, a digital health platform built to manage chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes), can rapidly build and scale digital health platforms. Livongo, for example, was founded in 2008 and IPO’d in 2019 to the tune of a ~$3B market cap (now ~$2B, but that’s a discussion for a finance course on the game between private and public markets).

Non-traditional healthcare players

By now, we have all caught wind of Amazon’s interest in healthcare. This interest dates back decades, with an initial ~$30-40M investment in Drugstore.com in 1999. Now, it is clear that Amazon views healthcare as a strategic industry to bet on, following a ~$753M purchase of PillPack in 2018. In that same year, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JPM Chase announced a heavily publicized joint venture: “Haven”. Amazon may represent the tip of the spear for non-traditional healthcare entrants. Strategic bets by non-healthcare enterprises have high potential, given their unique tech capabilities and assets long-held within healthcare giants ranging from: real estate to logistics through workforce management. Beyond those core capabilities, new players are familiar with low overhead, tech-enabled business models, which healthcare desperately needs. While large splashes draw attention, we share an equal excitement for start-ups and nascent ventures. This trend toward widespread capital access fundamentally shifts the power structure. Whereas in the past, medical care delivery was reserved for asset-rich corporations who could afford to build new hospitals and centers, now the trend to digital, combined with an increasing investor willingness to take risks on new business models, enables a software developer to launch a predictive analytics wellness business in her garage. Figure 7 (above) “Annual tech participation in healthcare” shows the increasing general activity, while Figure 8 (below) shows the numerous bets that Google Ventures, Apple, Microsoft and others are making as they seek to meaningfully break into the healthcare market.

Conclusion

So what does this all mean? Well, strategies must change. In order to retain their foothold, large healthcare players must consider new approaches to incubate business capabilities. New entrants must be strategic about who they partner with. Traditional VC investors must (1) facilitate high-quality, early stage deal flow to identify businesses at appropriate stages, valuations, and success probabilities and (2) must reach beyond simple investment dynamics to facilitate a more robust set of resources for new healthcare entrepreneurs who might be wandering blind in the complex healthcare ecosystem. We look forward to welcoming several VC and CVC executives to our conference to dialogue about their own unique approaches and perspectives on the future of healthcare investing.

Come to our 20th annual Kellogg Business of Healthcare Conference (BHC) on January 25th, 2020 to learn how various players in the healthcare industry, CVC, and tech are approaching market opportunities in different ways and what the future might hold.

About the Authors:

Ned Moffat is in his 2nd year at Kellogg in the full-time MBA program. Prior to Kellogg, Ned worked for L.E.K. Consulting as a MedTech dedicated Senior Associate Consultant supporting top medical device companies on key management issues. Additionally, he has experience advising Private Equity clients on buy side & sell side due diligence in medical devices and in broader healthcare. For his MBA internship, Ned joined Abbott Laboratories corporate ventures team and supported diligence and market assessments for multiple divisions. For the Kellogg Business of Healthcare Conference, Ned is helping the Marketing team find and form new partnerships with other MBA programs and engage non-traditionally healthcare focused students from Tech and EVC clubs as well as Kellogg alumni.

Tom Hittinger is also a 2nd year full-time MBA student at Kellogg. Before Kellogg, Tom worked in Deloitte’s Life Sciences & Healthcare Strategy & Operations Consulting group, advising cross-sector clients on capability transformations. Recently, Tom has contributed to early- and growth-stage healthcare investing & scaling efforts at OCA Ventures and UnitedHealth Group Ventures. Tom co-leads this year’s Business of Healthcare Conference, and is particularly enthusiastic about bringing new entrepreneurial perspectives to this year’s keynotes & panels.